Paid to cry

Have you ever paid someone to cry for you? Exploring the value of keening - an ancient form of ritualized grief.

Imagine passing by a funeral procession, pall bearers carrying a casket out of a church en-route to its final destination. Not so uncommon a sight, right?

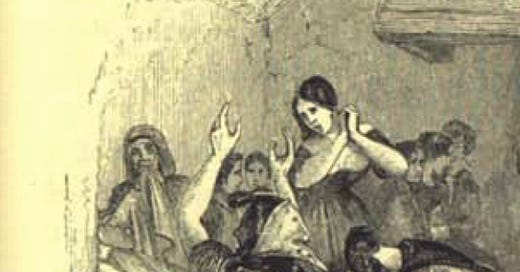

Now, imagine that as you pass, you see women wailing as they walk behind the casket - screaming and crying, tearing at their clothes even. And as you watch, one by one, other attendees of the funeral begin sobbing and behaving in a similar manner. Imagine spirited songs breaking out, wild, almost performative heartbreak, lamenting the loss and praising the attributes of the deceased.

What would you think?

Would you try to avoid eye contact and move on as quickly as possible? Or would you join in?

Would you think there was some kind of mass hysteria going on, or a mass healing?

At one time, not all that long ago, in Ireland and the highlands of Scotland at least, this wasn't all that uncommon a sight.

And if you were part of that community, you would probably join in, because you would believe that this process of communal, ritual grieving on Earth was necessary for the soul of the departed to cross over fully to the community of the dead. And you would know that those women, the keeners, were tapping into a very powerful, and necessary, source of inspiration.

You would know that their role was very important and respected. You might almost fear their ability to work in the thin space between life and death. But ultimately, you'd know that their ability to help everyone in the community properly grieve a loss was a source of healing medicine.

“…keens contained raw, unearthly emotion, spontaneous word, repeated motifs, crying, and elements of song…”

The word keening is an anglicized form of the Gaelic word ‘caoineadh,’ meaning ‘to cry.’ By all accounts, keeners were women, and in ancient times practiced in groups of three or more.

According to keeningwake.com, the website detailing a project to revive the ancient practice, keens contained raw, unearthly emotion, spontaneous word, repeated motifs, crying, and elements of song.

"Many believed the act of keening enabled a deceased soul to leave the body, and that keening was required, thus giving the role huge importance," the website says.

In fact, the role was so important and the women so respected that they often possessed huge political sway, and influenced, in the background, matters of state, according to the book, Historical Memoirs of the Irish Bards.

The book explains that the practice of keening was a calculated one, intended to inspire a heightening of melancholy at funerals, but also animating soldiers about to enter into battle - assuming “frantic airs,” like the British bardesses at these times.

And yet, no recording of the original form of keening exists. Though the practice was still performed in some parts of Ireland and in the highlands of Scotland around the mid-late 18th century, it was already touched by modernity and deviated from its original form.

According to Historical Memoirs of the Irish Bards, written in 1786, that last and most recent version of keening existed "so remotely from the original institution, so debased by extemporaneous composition and so disagreeable from unequal tones that no passion is excited. It is at present a truly barbarous but innocent custom.”

This recording contains the last recorded keen from the island of Inishmore, recorded in the mid 1900s. It displays some of the raw emotions of original keens, and yet, any recorded keen we have available to us today was likely not performed by a professional keener.

Déirdre ní mhathúna, a member of Keening Wake and artist behind a multimedia installation at The Burren exploring keening in 2007, asks the same question we at Full Circle ask: What is keening, really? Can we know the original form, or only imagine? We also wonder, in what ways keening has evolved - and what place it has today in Irish and Scottish society.

From Ní mhathúna's website: “What is a keening? Listening out for its echo…connecting with its purpose. Lifting it from its dusty-jacket and singing until our ancestral, unlettered song breaks through.”

Despite the lack of original examples, Ní mhathúna and other members of Keening Wake are creating and performing new keens - reviving and perhaps reimagining the practice and participating in propelling the evolution of keening into the future.

“…we also ask what the keening revival may mean for a parallel modern revival of a healthier relationship with grief…”

And so we also ask what the keening revival may mean for a parallel modern revival of a healthier relationship with grief. We also wonder what science has to say about using the voice as a modality to process emotions. (Stay tuned for our interview with modern, professional vocal healer Kimberly Joy Riely to find out just that!)

These questions, and more, we hope to answer in the coming months as we research, connect with professionals, and eventually travel to Ireland and Scotland to further investigate keening, among other topics.

So stay tuned, let us know what you think, and let us know what questions you have about this to be part of our investigations into keening and more about the Irish way of aging, ailing, end-of-life, and grief.

Thank you for reading! Please subscribe to this Substack and check out our socials for more inspiration, education, support, and community around aging, ailing, end-of-life, and grief.

If you would like to support this project you can also buy us a coffee at www.buymeacoffee.com/WalkingHome

Join our community!

E-mail submissions of artwork and writing for our online and printed magazine “Full Circle by WalkingHome.org”, or feedback and suggestions, to info@walkinghome.org

Follow us on instagram @walking_home_together and Facebook